Why the GCC’s green economy depends on fair wages

The Gulf region’s economic ascent has long been underpinned by access to low-cost labour. Migrant workers have powered the construction of skylines, serviced booming hospitality sectors, and supported households across the region. For decades, this model provided a competitive advantage: rapid development at low cost.

But as Gulf Cooperation Council countries transition toward diversified, knowledge-based economies—and increasingly engages with global Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) expectations—questions are emerging about whether its labour market structures are fit for the future. Among the most pressing: should countries in the GCC define and enforce a minimum or living wage?

The current landscape

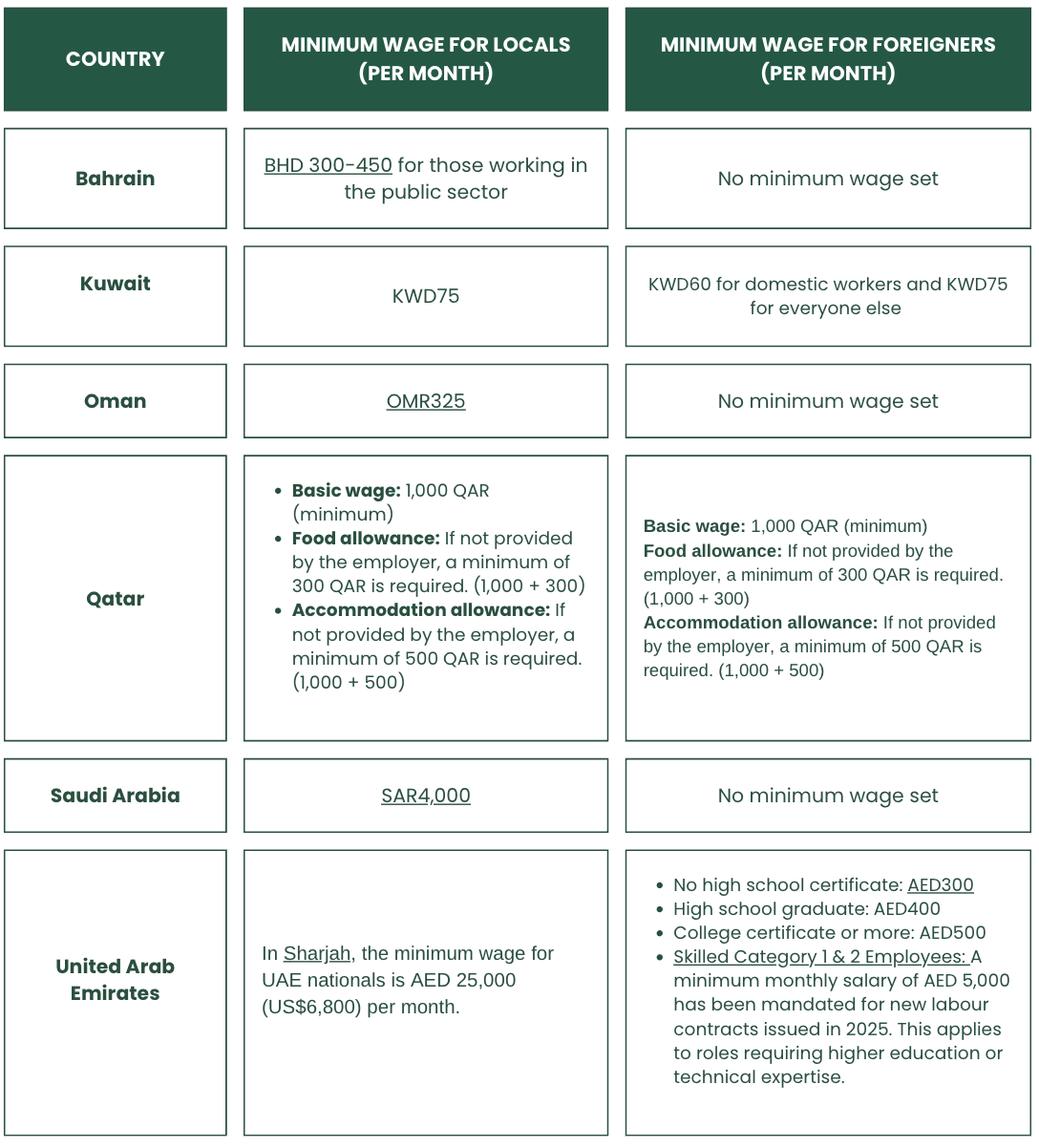

Today, wage regulation in the GCC is patchy. Some countries such as Qatar and Saudi Arabia have introduced minimum wages for certain categories of workers. While in some countries, like Saudi Arabia, these policies only apply to nationals, in others they also include migrant labour. However, implementation remains uneven, and no country in the region has adopted a universal standard aligned with local cost of living.

In many sectors, especially domestic work and construction, wages often fall far below what would be considered a decent standard of living. Workers frequently rely on shared accommodation, informal loans, or overtime just to cover basic needs.

Why it matters for businesses

1. Nationalisation goals

GCC countries are working to increase citizen participation in the workforce through policies like ‘Emiratisation’ and ‘Saudisation’. But the significant wage differential between citizens and migrant workers makes private sector hiring of locals economically unattractive. A fair wage ‘floor’ can help close this gap—making it more viable to recruit nationals and to reduce reliance on low-cost foreign labour.

2. Skills and productivity

Wage suppression often discourages employers from investing in workforce development. When labour is cheap, there’s little incentive to prioritise skills or productivity. A living wage model can act as a lever to shift hiring practices—rewarding capabilities, fostering upskilling, and ultimately improving output quality.

3. Worker welfare and stability

Low wages are often tied to poor working conditions, lack of mobility, and social exclusion. This increases the risk of worker dissatisfaction, visa overstays, and participation in informal economies. Establishing a living wage reduces these risks, improving social cohesion and long-term economic resilience. For businesses, market performance accelerates when workers thrive.

4. Global perception and investment

In a world of rising ESG scrutiny, investors, buyers, and multinational partners are increasingly evaluating how companies treat their workers. Major asset managers such as BlackRock and Norges Bank have signalled that labour practices, including wage fairness, factor into investment decisions. Large buyers in retail and hospitality are setting minimum labour standards for suppliers, including living wage requirements in ethical sourcing audits. Initiatives like the UN Global Compact and the World Benchmarking Alliance have begun to publicly rank companies and countries on social sustainability metrics. In this environment, jurisdictions that lack wage protections face reputational and commercial risks, while those with fair labour standards are more likely to attract long-term, responsible investment.

5. Cultural stigmas and workplace integration

In many sectors dominated by low-paid migrant labour, workplace environments can become culturally segregated. This often reinforces social stigma and discourages local nationals—particularly youth and women—from entering these roles, even when they match their skills or aspirations. Establishing a wage floor can help rebalance workforce composition, enhance perceptions of job dignity, and create more inclusive, integrated work environments where local workers and migrants participate on more equitable terms.

A phased approach to reform

Encouraging each GCC country to adopt a minimum or living wage is not without complexity. Cost of living differs across and within national borders, meaning wage benchmarks must be locally tailored. Small and medium-sized enterprises may struggle to absorb higher wage requirements without support. And without strong monitoring and enforcement mechanisms, even well-intentioned policies risk falling short of their impact.

Yet these are not insurmountable barriers. A phased, evidence-based approach could include:

Cost of living assessments for key urban centres

Sector-specific pilots to test wage thresholds

Public-private collaboration to co-design wage frameworks

Stronger enforcement mechanisms, using digital payment and contract systems

ILO’s newly updated living wage methodology provides a practical starting point. It helps employers and policymakers estimate wage thresholds based on real costs—not just market norms.

The role of business

Policy reform takes time—but business action doesn’t have to wait. Leading companies can take voluntary steps to define and implement living wages within their operations and supply chains. Doing so signals a commitment to responsible business practices, which can enhance brand reputation, strengthen relationships with international clients, and improve workforce retention.

This could include:

Benchmarking wages to cost-of-living indicators

Integrating living wages into supplier codes of conduct

Publicly reporting wage policies as part of ESG disclosures

Some businesses are already demonstrating what this can look like in practice. For example, Unilever has spent more than a decade embedding living wage principles across its global operations and key suppliers. Their approach has included setting clear wage benchmarks, engaging suppliers in collaborative improvement plans, and transparently reporting progress. The company reports benefits ranging from more resilient supply chains to stronger brand trust in key markets.

Industry-wide initiatives—particularly in sectors like construction, hospitality, and logistics—could also play a pivotal role in setting shared expectations and avoiding a race to the bottom. For instance, the Building Responsibly coalition brings together global engineering and construction firms to improve labour conditions in their operations and supply chains, with a focus on worker welfare. Moreover, voluntary global accreditations, provided by organisations such as the Living Wage Foundation, allow companies to demonstrate a commitment to their employees' well-being beyond legal requirements.

Building a future-ready economy

For countries in the GCC, introducing a minimum or living wage is not just about labour rights, it’s about shaping a more inclusive, skilled, and future-ready economy. The region has shown boldness in embracing economic transformation. Setting fair wage standards could be the next frontier in aligning that transformation with sustainable development and global leadership.

Marian Fletcher serves as Gulf Sustain’s GCC Local Advisor, bringing deep experience in labour market reform, sustainable supply chains, and ESG. In addition to her role with Gulf Sustain, she is an adjunct lecturer in sustainability, board advisor to a local NGO, and runs the GCC’s largest sustainability community.